Danilo Gallinari, the Denver Nuggets, and Man’s Best Friend

November 15, 2012 Leave a comment

As I said back on August 30, 2012 in part I of my three-part series on the Arron Afflalo trade, I do not enjoy making reason of chaos. This continues to be the case. There is just too much wrong with the Denver Nuggets for my personal lifestyle to keep up. This is the main reason why my writing has taken a dip of late. I have too many other commitments to be spending an incalculable number of hours processing and illuminating the incomprehensible inadequacies of this organization and then postulating how I would have done things differently. And until an NBA team decides my abilities are worth their time and money, my abbreviated outrage on Twitter will remain.

That said, prior to the season starting, people were interested in my ideas on how the Nuggets could make their new roster of players work, rather than the litany of ways in which it would not. In response, I had to tell them there was no way of it working. Eight games into the season, we have seen a validation of my hypothesis. And that’s sad, mostly because people being paid hundreds of thousands of dollars per year (if not more) are being tasked with making decisions I am better able to make in a few hours from my laptop at home for nothing.

The word “compulsive” describes the repetitive, irresistible urge to perform a behavior. A dog who displays compulsive behavior repeatedly performs one or more behaviors over and over, to the extent that it interferes with his normal life. The behavior he’s doing doesn’t seem to have any purpose, but he’s compelled to do it anyway. Some dogs will spend almost all their waking hours engaging in repetitive behaviors. They might lose weight, suffer from exhaustion and even physically injure themselves. Dogs display many different kinds of compulsions, such as spinning, pacing, tail chasing, fly snapping, barking, shadow or light chasing, excessive licking and toy fixation. It’s important to note that normal dogs also engage in behaviors like barking and licking, but they usually do so in response to specific triggers.

Courtesy: WebMD

In what comes as a shock to many, the Denver Nuggets (with one of the league’s lighter schedules) are a middling team through eight games of the 2012-13 season. In what should come as zero shock to my faithful readers, I am not surprised. Now, with Denver struggling to keep their head above water, throngs of Nuggets’ fans have began calling for more trades. Surprise, surprise. The dog is chasing its tail again.

On June 22, 2012, I wrote:

At what point do the players traded stop being the scapegoat and the people in charge of moving them take responsibility? When is the franchise going to have any form of stability? When will their best players be identified and then be held onto for the duration of their careers?

Since June 22, the Denver Nuggets have done nothing to stem the tide of tail-chasing. Instead, they’ve involved themselves in yet more trades. And the dog goes round and round again.

During the NBA’s draft on June 28, Denver took swing-man Evan Fournier out of France with the 22nd overall pick. I guess Wilson Chandler, Danilo Gallinari, Arron Afflalo, Jordan Hamilton, and Corey Brewer weren’t quite enough to satiate their appetite for wing players. With only Kenneth Faried and Al Harrington on the roster at power forward, common sense would dictate Nuggets brass look for a backup power forward. Jared Sullinger, whom I advocated they take with their first overall pick (if they weren’t going to trade up for Iowa State’s Royce White — who I had no idea would refuse traveling with his team after signing an NBA contract), went to the Celtics immediately after Denver took Fournier.

During the NBA’s draft on June 28, Denver took swing-man Evan Fournier out of France with the 22nd overall pick. I guess Wilson Chandler, Danilo Gallinari, Arron Afflalo, Jordan Hamilton, and Corey Brewer weren’t quite enough to satiate their appetite for wing players. With only Kenneth Faried and Al Harrington on the roster at power forward, common sense would dictate Nuggets brass look for a backup power forward. Jared Sullinger, whom I advocated they take with their first overall pick (if they weren’t going to trade up for Iowa State’s Royce White — who I had no idea would refuse traveling with his team after signing an NBA contract), went to the Celtics immediately after Denver took Fournier.

The Nuggets further compounded their basketball inadequacies by taking Quincy Miller during the second round. I said on Twitter during the lead-up to the draft that if Denver decided to take Miller at any point I would “laugh my ass off in anger.” I was forever grateful they didn’t take him during the first round, but, became amused when they predictably did during the second. He’s a nice player — puts up nice numbers — until you actually watch him play, an activity by which it seems Denver’s front office very rarely partakes. How else would you explain drafting Kenneth Faried in 2011 and following it up by trading for JaVale McGee? Anyone who actually watches basketball knew those two wouldn’t mesh. Everyone except Denver, I guess. How else would you explain the Nuggets then trading their only shooter this past summer for yet another diverse wing in Andre Iguodala? Anyone who actually watches basketball knew that wouldn’t work. Everyone except Denver (Kevin Pelton, John Hollinger, and their echo chamber), I guess.

When NBA executives begin using the ever-elusive “productivity” to build their team, they’ve lost before even getting started. Which is why the cacophony of basketball illiterates is at it again. Everyone wants to trade Danilo Gallinari, one year removed from being what many called the third-best small forward in basketball (behind LeBron James and Kevin Durant; sorry Knicks’ fans, even ahead of Carmelo Anthony). Everyone wants to move Gallinari because he’s neither shooting the ball well nor getting to the free throw line with nearly the frequency he’s accustomed to throughout his career.

Fancy that. When the Nuggets traded their only shooter in Arron Afflalo this summer for Andre Iguodala, it forced Denver to move Gallinari into a supporting role as a shooter — something he’s not built to do. Not surprisingly, I made this point immediately following the trade. Not only did Denver hinder Gallo’s development first by trading Nene for JaVale McGee, they further compounded their basketball inadequacies by trading the only shooter on the roster for a player four-years older, four-inches shorter, and with a similar skill-set to their 24 year-old, 6-foot-10, Italian phenom. The ignorance is so breathtaking it’s palpable.

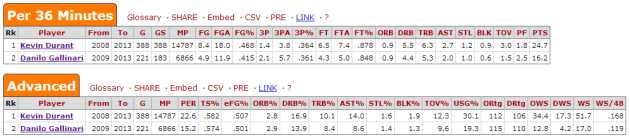

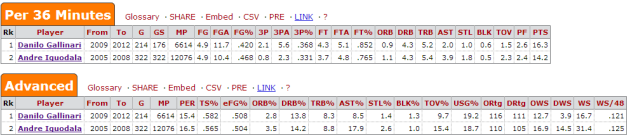

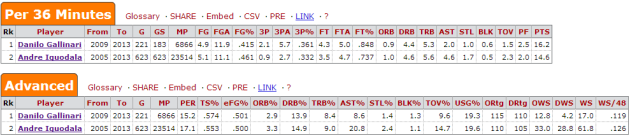

Danilo Gallinari is 24 years-old and in his fifth NBA season. Andre Iguodala is 28 and in his ninth NBA season. Danilo Gallinari is a 6-foot-10, 225-pound point guard in a forward’s body, who can rebound, dish, and shoot at an elite level in the right situation. Andre Iguodala is a 6-foot-6, 202-pound tweener at shooting guard and small forward. He can’t shoot well enough to be a prototypical shooting guard. And he’s not big enough to line up at small forward and be defended by bigger, taller, longer opposing players (like those he’d face in Gallinari and Durant). Danilo Gallinari averages about half the assists and half the steals of his new teammate, but he’s nearly ten points better than Iguodala at the free-throw line and nearly four points better from three. Gallinari also turns the ball over at nearly half the rate of Andre Iguodala. Their respective effective field goal percentages (EFG%) are naturally similar, however, Gallinari has a far superior true shooting percentage (TS%). Other than that, they’re objectively the same player. Gallinari is merely able to do the same things in a much bigger body, which, in basketball, is kind of a big deal. (Oh, another pretty big deal? Gallinari is just now entering his prime. He can still become a better player. Andre Iguodala is on the downswing. Age and size are kind of important in basketball. Shocking, I know.)

If those numbers aren’t enough for your brains to wrap around, here’s more:

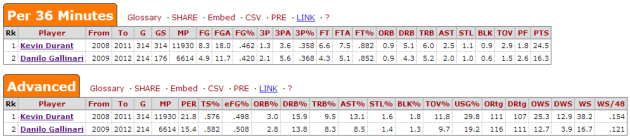

According to 82games.com’s on-court/off-court statistics for the 2011-12 season, Danilo Gallinari had a better year (per 100 possessions) than Kevin Durant (see below), James Harden, Russell Westbrook, Dwyane Wade, Rudy Gay, Andre Iguodala (see below), Carmelo Anthony (see below), Nicolas Batum, Luol Deng, Paul Pierce, Josh Smith and countless others. Furthermore, Gallo’s on-court/off-court statistics are steady throughout his career. His 2010-11 season is somewhat skewed because it’s the year he was traded from New York to Denver. However, if you look at his 2009-10 season, it is better than Durant’s 2011-12 iteration — when KD is arguably as good as he will ever be.

How do Durant and Gallinari compare statistically? They’re scarily similar.

Danilo Gallinari – Kevin Durant player comparison–2012-2013 season included (Courtesy: Basketball-Reference)

The NBA is fast becoming a league where every team has the same exact data at their disposal when making decisions. The front offices that find success are those that understand the data better than the rest, and hence, put it to use in a much more academic manner. Some basketball-stat folks are now saying they “aren’t quite sold on Danilo Gallinari”. Meanwhile …

So, to recap: the Nuggets traded a player they were asking far too much of in the first place (Afflalo) for a player who has the same skill set as the best young asset they received in the Carmelo Anthony deal (Danilo Gallinari). They then expected Gallinari to take over for Afflalo’s role shooting the basketball (something he’s not equipped to do), while moving Iguodala into Afflalo’s starting spot in the rotation. Then they expected Iguodala to manufacture the same production he’s historically known for, while being surrounded by a team of players not complementary to his skills in the least.

If any of that makes sense to you, then you would also be able to make sense of playing a 6-foot-11, 260-pound beast (and natural power forward) at center for nine years. If any of that makes sense to you, then you would also be able to make sense of a team trading that same beast (even if he is oft-injured) for JaVale McGee. If any of that makes sense to you, then you would also be able to make sense of a team offering a fairly generous contract extension to an undersized starting point guard who lacks both a mid-range jumper and floater — two skills found in nearly every starting point guard in today’s NBA and an absolute necessity if your franchise is in earnest pursuit of success. If any of that makes sense to you, you probably spend more of your time staring at a spreadsheet than you do basketball players playing basketball games. If any of that makes sense to you, then you would probably be fine making the decisions for a team that never gets out of the first round of the playoffs, because … you would be running it.

And if any of that makes sense to you, you would probably chase your tail incessantly as a dog until you collapsed from exhaustion. That’s why dogs have owners — to discipline them and ensure they cease with the compulsive activity. If and when they don’t stop the tail-chasing, the responsible dog owner has three options:

- Keep the dog, love the dog, and put up with the poor thing until it dies.

- Put the dog up for adoption, knowing full well that another family is unlikely to bring it into their home with its affliction.

- Put the dog down.

It might be time to put the dog down.

You set yourself back ten years (arbitrarily speaking) by trading Nene for JaVale McGee. You’ve set yourself back at least another five years by trading Arron Afflalo for Andre Iguodala. And you will set yourself back a further ten years beyond that (if not more) by trading Danilo Gallinari. It shouldn’t be that difficult to find and maintain success in the NBA, what with the dearth of talent that exists throughout the league. You just can’t be … the runt of the litter.

Is there a way to fix this roster and maybe get them winning more games this season? I do not know. If so, it would take a drastic change in direction and philosophy — something George Karl and his staff have never seemed to embrace.

You must be logged in to post a comment.