Context, size, spacing (and the Cosmos) matter in the game of basketball

October 11, 2012 Leave a comment

Before moving forward I would like to address the entirety of the world that has had the (mis?)fortune of reading this blog. Have I been overly critical of Denver’s front office? Yes. Unfairly so? Possibly, yes. Bordering on psychosis? Maybe. Much of this criticism–actually, no, all of this criticism–is rooted in the Nene for JaVale McGee swap. Trading a good player for a bad player is bad basketball. It’s not because Nene was my favorite Nugget. It’s not because I still have a man-crush on the Brazilian (even though I do). It’s because trading an already good player for potential alone is foolish. I don’t care how many games Nene sits due to minor injuries. Trading a heady, professional with high on and off-court I.Q. for the absolute opposite is insane. And anyone who says most teams in Denver’s position would have done likewise is marking out. Period. JaVale McGee is not good. Nor will he ever become good. He, like J.R. Smith before him, doesn’t have the mental fortitude or aptitude to turn his raw potential into the goldmine it could become. It’s not Nene. It’s never been about Nene. It’s JaVale. It’s just, JaVale. If a guy doesn’t get “it” when he starts playing, he’ll never get “it” at all. You can blame Washington and Ernie Grunfeld all you want, just know ahead of time that a player makes his situation. The environment doesn’t have to make the player. Outside of a select few, every other Wizards teammate of JaVale’s didn’t have the same irrevocably disturbing habits. JaVale could have done better there in the same way he can do better here — starting with his eating habits. Having said that, I am also critical because I do not adjust to change very well–particularly change that manifests into JaVale McGee. Very few franchises have gone through as much change over the last decade as this one. In that same vein, very few franchises have also won as many games. It would be nice if the constant whirlwind of roster movement stopped for players, coaches, and fans alike. Just make sure to keep winning games, okay? And do something about JaVale. Winning doesn’t get old. At least I don’t think. JaVale already has.

When running a team in what is perceived to be one of the NBA’s smallest markets, a front office has to be smarter than pretty much all of its competitors in order to attain and maintain excellence. Their margin for error is so nonexistent that it puts everything they do under a microscope. Mistakes can’t happen. Draft picks must be thoroughly scrutinized. Potential trades require extensive discussion.

Throughout our study of Denver’s involvement in the Dwight Howard trade, it seems as if Nuggets’ management might not have abode by this proxy. As a result, they now have a roster chock-full of disjointed talent, skill overlap, little reliable shooting, and loads of athleticism. But boy, can they produce. They’re like a fantasy team in their production capabilities. This is why a lot of very smart people are picking them as a dark horse candidate to dethrone the Thunder from the Western Conference’s elite. They’re taking Iguodala’s career numbers as a Sixer, his rightfully warranted reputation as an all-world defender, coupling it with each individual Denver Nugget player’s career production, taking the same model from each individual NBA member team, and combining it all into one nice, messy, long equation; and voila, 58-wins.

CONTEXT MATTERS

The problem with applying this equation to basketball is that basketball is a game played in space by ten individual actors at one time. Each of these actors is not subject to variance like you’d see in every other statistical simulation because they are doing more than driving the numbers. They are the numbers. These actors are human beings. Each human being is not alike. Some are taller. Some are broader. Some are longer. Some are more skilled. Some are smarter. Some are dumber. Some are more clumsy than the other. They’re not a roll of the dice. They’re not a stack of cards. A team of players is not constant. Human beings themselves are not constant. We are fluid. Literally.

There’s a reason one player performs better or worse than another player in much the same way there’s a reason we know not to touch a hot stove. There’s a reason player A appears to be less efficient than player B. If player A’s teammates are not very good, he will have less space to apply his craft, and thus, appear to be inefficient in doing so. But we do not count a player’s teammates in each individual assessment. Because that would make the already insanely complex even more-so. That’s not random variance. That’s not a flaw in the player. That’s a flaw in the system by which each individual player is measured and, by extension, expected to perform. Spacing matters. Size matters. Context matters.

Player size is just one of many variables that influence the box score. When Pau Gasol is able to tower over Kenneth Faried for a rebound despite a fundamentally sound box-out by the Manimal, no one really notices. Faried earned himself a double-double in the box score, after all. When David Lee has the ball on the high-post and is looking down on Faried, Lee’s chances of making a simple jump-shot increase ten-fold because there is very little impeding his line of site to the rim. No one really notices this, though, because Faried’s going to put up 15-and-10. The fact he can’t stop an opposing player due to his size matters little. Production. Production. Production.

When Ty Lawson faces a hard hedge on a pick-and-roll that becomes a double-team and he turns the ball over because he’s not big enough or long enough to pass out of it, no one really notices. The box score shows he played great. When Kenneth Faried can’t stop an opposing player in space because he doesn’t take up enough of it, no one really notices. All they see is the 12-and-10. When Jerry Sloan inserts big man Kyrylo Fesenko into his starting lineup for game two of Denver’s 2010 first round playoff series against the Utah Jazz and the whole kit and caboodle turns in Utah’s favor, no one really notices. The box score says Nene played great and Fesenko proved ineffective. Nene produced, after all. It must mean he’s a center.

If you watch the Denver Nuggets as closely as I do you’d see these guys playing as hard as they possibly can. You can see and hear as Kenneth Faried screams in anguish during a box-out where he’s surrounded by two and three players twice his size against the Oklahoma City Thunder. You can see as Ty Lawson drives the lane against the Los Angeles Clippers only to be surrounded by a crowd of human flesh three-times his size hell-bent on keeping him from the rim. You can see the difficulty with which Lawson is faced when attempting his set jump-shot against a towering opponent’s close-out. People don’t understand the task Denver’s management is asking of these players–Lawson and Faried in particular. In a game overflowing with Goliaths, Denver is intent on running David into the ground. It makes me uncomfortable seeing such undersized players be asked to do so much.

Sure, they are professional athletes. But even the most finely-tuned athlete cannot make up for disparities in size. Play Ty Lawson 35+ minutes per night and see his body wear down from the unending punishment he’s likely to endure. Lawson puts his body on the line more than any player I’ve seen in a Nuggets uniform since Iverson. Play Kenneth Faried 35+ minutes per night and watch a young man’s body detonate before your very eyes. A player can only withstand so much before breaking down.

This is basketball. Basketball is a sport. An athletic competition between a team of individuals. When a wide-receiver towers over an undersized cornerback to grab a football, a color commentator is quick to point out how smart the quarterback was in picking out a matchup advantage and attacking it. When Kevin McHale’s Houston Rockets come out in April of last year and pound the ball into Luis Scola at the game’s outset because Kenneth Faried has little chance of stopping him, no one notices. After all, Faried put up 10-and-11 the night before against the very same team, right? That he could not contain Scola either night isn’t mentioned. Context matters. Spacing matters. Size matters.

Size matters just as much in basketball as it does in every other sport sans golf and tennis. And maybe ice-fishing. When the two most important players on a basketball team are as undersized at their positions as Lawson and Faried, you’re giving yourself no chance of competing against the league’s elite. And if people don’t understand how Lawson and Faried are undersized at their positions, I cannot help them. It’s basketball. One undersized player per rotation is fine. Two? You’re just asking for trouble. Production over size is foolhardy seeing as the very game they play is defined by the space in which it is contested. This isn’t rocket science. It’s simply physics. Inches matter.

I’m sure many will disagree. Many will say the game is defined by the scoreboard. Which is true. But what appears on the scoreboard is defined by what happens on the floor. And what happens on the floor is defined by the space in which it is played. The space in which it is played dictates how each individual actor engages in the activity. And what defines each individual actor is size, speed, skill, and smarts. Nothing is as simple as it seems. Especially not basketball.

TAKING INVENTORY

With that said, one thing you have to do after a major trade before moving forward is take inventory; see what you’ve given up, see what you’ve added to replace it, and then see what’s remaining to build around. That is all I have done over the last few weeks with the Denver Nuggets. They gave up a young, competent, insanely efficient, first-in-his-class shooting guard, for an all-world defender, first-in-his-class facilitator, and what history suggests to be a ‘meh’ shooter. History, like anything (including myself), can be very, very wrong from time-to-time.

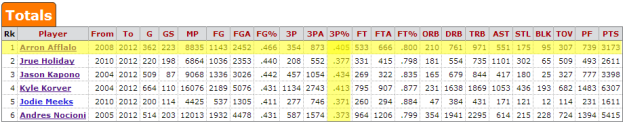

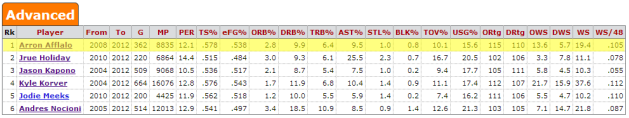

My biggest fear is Denver nullified the trade’s potential success by moving the only player who makes Andre Iguoadala the player he is, while further hampering Danilo Gallinari’s growth as a point-forward. Throughout his career, Andre Iguodala has had the luxury of being surrounded by great shooters like Kyle Korver, Jason Kapono, Jrue Holiday, and Elton Brand. These are players who may not have always excelled from three, even though there were many, but did so from mid-range as well. As such, one reason Iggy’s assist rate is so high is because of those shooters. This theory could be false. Danilo Gallinari’s assist rate rose six points last year to a career high and it’s not like the Nuggets had a treasure trove of shooters. Well, except for the one. However, if Denver was going to trade anyone for Andre Iguodala, it should have been Gallinari, as Iguodala’s addition negates Gallo’s utility to a certain extent. The problem isn’t that Iguodala has no one to pass to. The problem is that Iguodala doesn’t have the shooters and floor-spacers he’s accustomed to. Arron Afflalo was one of those shooters.

Don’t be mistaken. Denver can, and likely will, still win some games. And they can win a whole hell of a lot of them. All is not lost (even though my doom and gloom over the last several months has made it seem so. I might be kind of nuts). I did, after all, pick them to miss the playoffs(!?).

In order to win, though, Denver’s coaching staff must take great pains in building lineups that complement each individual player on their roster. This is eminently more difficult than it seems because Denver is so undersized (at the game’s two most critical positions), there’s so much overlap in skill following the Afflalo-for-Iguodala swap, and two players for which they may be reliant are not up to par in the intelligence department. Player production isn’t something you pull out of a hat. Everything that happens on the floor dictates each individual’s stat-line. There’s a reason behind everything. Space matters. Size matters. Context matters.

There aren’t many games decided on player instinct alone. There are even fewer as complex as basketball. A baseball player knows exactly where he’s going to go when he knocks a hit into the outfield. Likewise, an outfielder knows before a pitch where he’s going to throw the ball if and when it comes his way. Basketball is not baseball. That’s why I love it. It’s totally and unabashedly random (with certain caveats). But that’s also why so few people actually get it. There are so many variables at play. A team can’t be built in a test-tube. Except, it kind of is.

I’ll reveal my test tube in the coming days and show you how the Denver Nuggets can force me into writing a public apology to Arturo Galletti of the Wages of Wins Network by winning over 47-games.

Until then, here’s a preview:

You must be logged in to post a comment.