On George Karl, Masai Ujiri, and what’s next for the Denver Nuggets

May 10, 2013 1 Comment

“If I give you a team that’s not super-talented, but, they care and try hard, I’m going to win 35-games with that team and you are going to love them. If I give you a super-talented team that doesn’t care that much, [and] that doesn’t try that hard, I’m going to win 50-games and you are going to hate them.”

– Kevin McHale on the Dan Le Batard Show paraphrasing the great, Red Auerbach

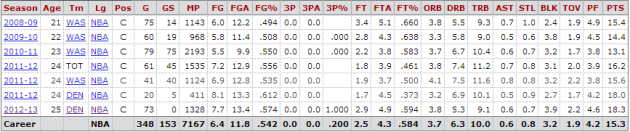

This quote is a corollary for George Karl’s entire tenure in Denver. When he was originally hired midway through the 2004-05 season, he led the Nuggets on a furious 32-8 finish with a super-talented core of Carmelo Anthony, Andre Miller, Marcus Camby, Kenyon Martin, and Nene Hilario. That team suffered a gentleman’s sweep at the hands of the eventual NBA Champion, San Antonio Spurs, in the first round.

The very next season, under a full-year of George Karl’s tutelage, the Nuggets again suffered a gentleman’s sweep, this time at the hands of the Los Angeles Clippers — a series and opponent that saw Denver favored. However, that team deserves a bit of a reprieve, as every member of their frontline (sans Carmelo Anthony) suffered through injury. Nene was lost in the first game for the entire season. Kenyon Martin and Marcus Camby each missed enough time to force Francisco Elson into starting 54 games. Ruben Patterson, DerMarr Johnson, and Greg Buckner each started 20, 21, and 27 games for Denver, respectively. Buckner, a league journeyman, played 1758 minutes that season — fourth-most on the team behind Anthony, Camby, and Miller. Elson, Patterson, Johnson, and Buckner seemingly fell off the Earth following their time in Denver.

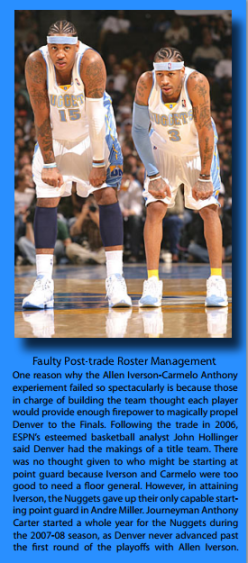

In 2006-07, the Nuggets again suffered through serious injuries, when Kenyon Martin was lost for the entire year during the season’s second game. Carmelo Anthony, Allen Iverson, Marcus Camby, Nene, and J.R. Smith once again provided a super-talented — albeit wholly unlikable — core that, according to most, underachieved. Like George Karl’s first Nuggets team, the 2007 iteration suffered a gentleman’s sweep at the hands of the eventual NBA Champion, San Antonio Spurs. What gets lost is Eduardo Najera (1658), Steve Blake (1642), Linas Kleiza (1488), Yakhouba Diawara (1177), and Reggie Evans (1127) each played significant minutes for Denver that season. Outside of Steve Blake’s brief stint in Los Angeles and Reggie Evans’ run in Brooklyn, none of those players have been seen or heard from since. Even Earl Boykins, at 30 years old, played 877 minutes that year.

The 2007-08 Nuggets, on the backs of Iverson and Anthony, were thought to be surefire contenders. That team, much like every single other Karl squad before it, befell to injuries, as Nene saw just 266 minutes in 16 games. Anthony, Iverson, Camby, and Martin formed a nice core. It’s just that 32 year-old Anthony Carter was their starting point guard. Carter (1960), Kleiza (1889), Najera (1664), and Diawara (542) each saw a significant chunk of minutes. None of them have been seen or heard from since. Only 22 year-old J.R. Smith had a future in the NBA. And he saw merely 1421 minutes that season — eighth-most on the team. The 2008 Nuggets were swept in a not-so-gentlemanly manner by the eventual NBA Finals runner-up, Los Angeles Lakers in the first round.

The only year where everything seemed to fall into place came in 2008-09, when Denver suffered no significant injuries. Those Nuggets made the Western Conference Finals. And if not for a few errant Anthony Carter passes, would have made the NBA Finals.

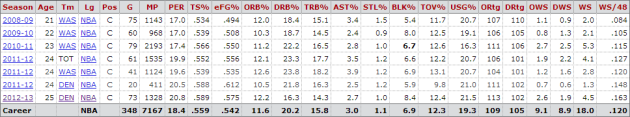

The 2009-10 Nuggets won 53 games and the Northwest Division. Outside of Kenyon Martin’s 58 games played, no Denver player suffered a significant injury. Anthony Carter only saw 859 minutes, as Ty Lawson proved to be just the change-of-pace backup Chauncey Billups needed. That team had similar dreams of its predecessor, and if not for George Karl’s cancer, might have made some playoff noise. Adrian Dantley, however, proved to be in way over his head, as the Nuggets lost in six games to the underdog, Utah Jazz.

The 2010-11 Nuggets — in my eyes the best Denver team outside of the Western Conference Finals squad — played the upstart Oklahoma City Thunder to five close games. If not for a phantom basket interference call on Nene in game one, they would have had a good chance winning the series. Every game was tight. That team could both shoot from three and the free-throw line. They had a threat on the interior in Nene and terrific perimeter defenders and scorers alike. Of course, that Nuggets team was forced to live through the entire “Melo-drama” trade fiasco. Raymond Felton, a 46% 3-point shooter during his short stint in Denver, was moved that offseason for the slower, more determined, and plodding Andre Miller. J.R. Smith and Kenyon Martin were allowed to walk.

Denver’s 2011-12 Nuggets’ team has been lauded for taking the Lakers to seven games in the first round, when that same Lakers team was quickly dispatched in five the very next round by the Oklahoma City Thunder. What gets further muddied in the annals of history is Ron Artest’s suspension (following his elbowing of James Harden during the regular season) cost him the first six games of that series. If Los Angeles had Metta World Peace from the series’ start, the Nuggets would have been lucky to see game six. As it was, if not for a ridiculous performance out of JaVale McGee, Denver was lucky to see game seven.

Which brings me to the 2012-13 season …

The Denver Nuggets were surreptitiously dispatched from the 2013 NBA Playoffs by the Golden State Warriors last week. Nuggets fans and bloggers alike are rightfully upset. The best season in franchise history was supposed to be different. 57 wins, the third seed, and homecourt advantage was supposed to mark a difference.

Naturally, everyone wants to lay blame at the feet of someone. Unfortunately, for a team without a “star”, the easiest person to blame is the head coach. George Karl deserves some blame. But, there’s plenty of it to go around.

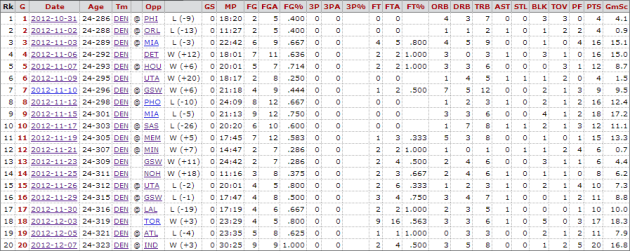

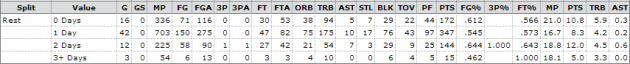

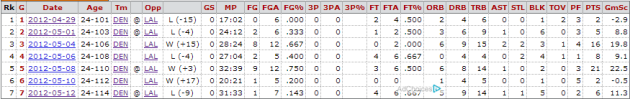

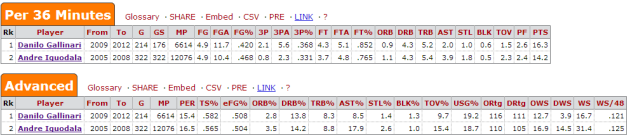

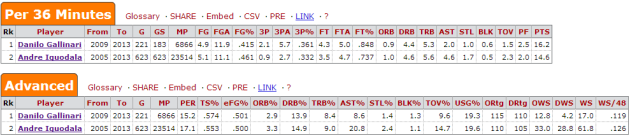

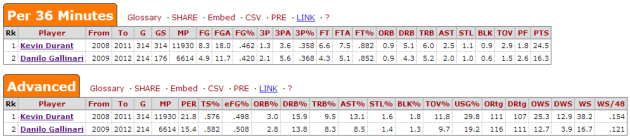

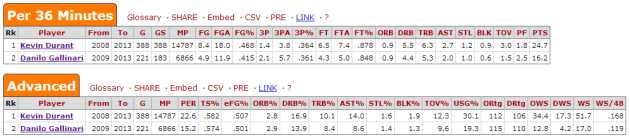

This team, like Karl’s first few Denver teams, suffered a devastating injury when Danilo Gallinari went down during the final week of the regular season. Many conveniently forget to mention that when writing the Nuggets’ 2012-13 season opus. Gallinari’s injury, while a convenient excuse, is a valid one. It put Denver’s entire rotation in flux and forced its head coach to give playoff minutes to players who wouldn’t have seen the court except in spot duty — players like Wilson Chandler, Anthony Randolph, Corey Brewer, and Evan Fournier.

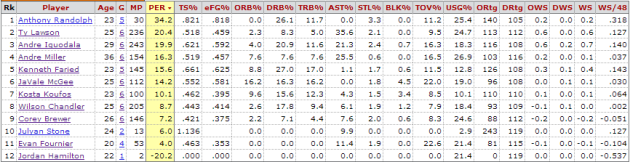

In six playoff games, Corey Brewer saw 146 minutes. He rolled up a PER (player efficiency rating) of 7.2 in that time. In Wilson Chandler’s 205 minutes, he tallied a PER of 8.7. In Evan Fournier’s 53 playoff minutes, he posted an overall PER of 4.0, while averaging four turnovers and four personal fouls per-36 minutes. These numbers aren’t just bad. They’re bone-chillingly bad. Denver’s other 2012 draft pick, Quincy Miller, couldn’t see the floor as he is nowhere near ready for the rigors of the NBA (and may never be). All the while, Mark Jackson was able to rely on rookies Harrison Barnes, Draymond Green, and Festus Ezili (two of which were taken after Fournier).

Even players who would have seen court time with a healthy Gallinari struggled. JaVale McGee, a PER-darling during the regular season, posted a rating of 14.2 in 112 playoff minutes. Kosta Koufos, Denver’s most underrated and unheralded player during the regular season, tallied a PER of 10.1 in 100 minutes. Denver’s lone draft day victory in Stan Kroenke’s entire tenure as owner, Kenneth Faried, posted a PER of 15.6 in 145 minutes — a far cry from the 18 he posted as a rookie in 2012.

PER is an incredibly flawed metric, to be sure. However, for the sake of brevity, it is a good overall gauge of player productivity.

For comparison’s sake, the Houston Rockets — a team many consider in the same league as Denver where it concerns youth and potential — had only two players fail to register a double-digit PER. Jeremy Lin, playing an injury-riddled 84 minutes, posted a negative PER of -0.6. James Anderson’s 18 minutes produced an overall PER of -1.6. Every other player on their playoff roster, including rookie Terrence Jones, Aaron Brooks, and Greg Smith (someone who had no business on a playoff basketball court), posted PER’s in the double-digits.

The Clippers had four players — Ryan Hollins, Grant Hill, DeAndre Jordan, and Chauncey Billups — each fail to register double-digit PER ratings. Only in DeAndre Jordan do they have a future invested. One other small detail: They have the best point guard in the world in Chris Paul and one of the league’s brightest, youngest, stars in Blake Griffin.

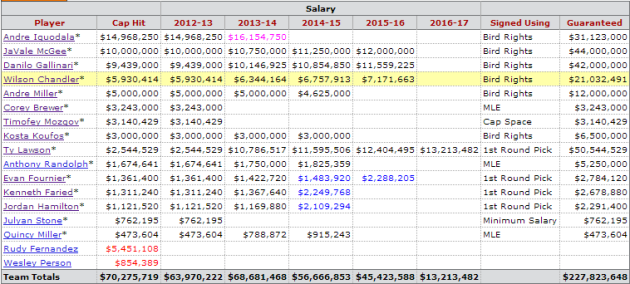

The Lakers had five players — Antawn Jamison, Chris Duhon, Metta World Peace, Jodie Meeks, and Earl Clark — fail to register double-digit PER this postseason. Wilson Chandler will earn $6.3 million next season, $6.8 million in 2014-15, and $7.2 million in 2015-16. Jordan Hill and Chris Duhon will earn a combined $7.4 million next season in Los Angeles — the end of their guaranteed contracts.

The Chicago Bulls had four players fail to register a double-digit PER in Luol Deng, Marquis Teague, Daequan Cook, and Richard ‘Rip’ Hamilton. Deng lost 15 pounds while laid-up in the hospital following complications from a spinal tap procedure last week. Marquis Teague is Chicago’s fourth-string point guard, and only seeing time because Derrick Rose and Kirk Hinrich are both injured — leaving only Nate Robinson available.

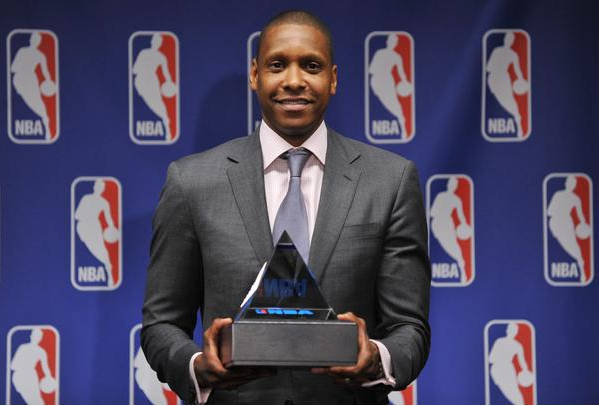

Masai Ujiri is very worthy of the Executive of the Year Award he received this season. He built a terrific regular season roster that won a Denver franchise-record, 57 games. However, when it comes to the playoffs, his team-building leaves much to be desired. And he’s just as culpable as anyone when it comes to laying blame for Denver’s first round flameout.

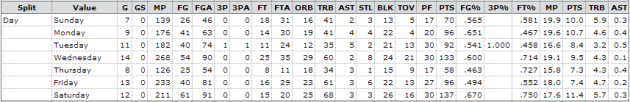

After all, it was Ujiri’s front office that didn’t address their team’s woeful shooting concerns. Say what you will about Stephen Curry’s super-stardom, but the Nuggets lost this series at the free throw line, the 3-point line, and on the perimeter. Game six, decided by four points, featured a Denver team that went 13-of-21 from the charity stripe — including a 2-of-7 performance from starting front court mates, JaVale McGee and Kenneth Faried. Even if Denver had been fortunate to get more whistles, they might not have been able to make them count. What’s more? The Nuggets shot a horrendous 25% (7-of-28) from the 3-point line in game six, with Ty Lawson, Wilson Chandler, Corey Brewer, and Andre Miller going a combined 1-for-20. If not for Andre Iguodala’s herculean 5-for-8 effort from three (and Kosta Koufos’s flukey 3-point make), the four-point margin would have been much, much greater.

Of the sixteen playoff participants, only the Pacers (31%), Clippers (30.4%), Lakers (27%), and Bucks (26.1%) shot worse from 3-point range than Denver (31.1%) during the postseason. The Clippers were bounced in six while both the Lakers and Bucks were swept. Furthermore, only Chicago (71.6%), Houston (71.1%), Atlanta (68.2%), Milwaukee (63%), and the Lakers (60.8%) shot worse from the free throw line than Denver (73%) during the playoffs. Houston and Atlanta both lost in six. The Nuggets were lucky to not have been swept in the same fashion as Milwaukee and Los Angeles.

Denver’s woeful shooting concerns notwithstanding, it was the same front office that didn’t shore up the Nuggets’ porous perimeter defense — outside of the patchwork trade for Iguodala during the summer. I have been very critical of Ty Lawson’s defense, and rightfully so. But the truth of the matter is no team with the undersized Lawson, the aged legs of Andre Miller, and the fundamentally deficient Kenneth Faried, JaVale McGee, and Corey Brewer should expect to defend well — even with Andre Iguodala wreaking havoc on the perimeter.

Sadly, the lionshare of the blame will sit at the foot of the head coach. He’s the one that led them to 57 regular season wins. He’s also the one that led them to a first round playoff loss for the eighth time in nine seasons. And he is the one that prematurely changed his entire rotation following game two, starting undersized and still hobbled power forward, Kenneth Faried, at center.

Denver’s best five-man unit in the playoffs saw only five total minutes together in the regular season because of Gallinari’s reign of good health. Ty Lawson, Andre Iguodala, Wilson Chandler, Kenneth Faried, and JaVale McGee played 22 total minutes together in the series. After their game five victory, where said lineup saw fourteen minutes, George Karl only gave them eight minutes in game six. Part of that had to do with Faried’s aforementioned foul trouble. But, as a head coach, you absolutely have to find time for a lineup that scored 110.5 points per 100 possessions while allowing just 87.7. Golden State had too much trouble countering Denver’s length and athleticism with those five on the floor.

Why did it take until game five for Karl to deploy that lineup? And why, after seeing its effectiveness, did he only give them eight minutes in a potential series-clinching game six? Removing Kenneth Faried is understandable. But, it’s certainly not advisable. Not when your playoff lives are on the line. However, therein lies the rub: How can George Karl possibly give players like Faried and McGee playoff minutes when they’re such poor free-throw shooters and ball-chasing defenders? Coaches aren’t dumb to opponent weaknesses. Not anymore. Smart coaches like Gregg Popovich and Scotty Brooks (gasp!) would eat Denver alive if they used such lineups.

Denver’s second-best five-man unit in the playoffs only saw four minutes together in the regular season. That lineup included Andre Miller, Ty Lawson, Andre Iguodala, Wilson Chandler, and JaVale McGee. They scored 104.5 points per 100 possessions while allowing only 94.6 in their 26 playoff minutes. What’s interesting is they saw action in all six games — just no consistent court time in anyone of those games. Why not? Why aren’t George Karl’s most effective lineups being used more often?

The Denver Nuggets don’t need a new head coach. They need a specialist able to identify their best lineups and advise George Karl on them properly. Is it any wonder that they’ve struggled in the playoffs since seeing stat man and ‘George Karl’s brain’, Dean Oliver, leave the team to join ESPN? I think not. Second, they need to clean house of the knuckleheads and get serious about winning a championship — if that is indeed their goal. If Denver’s free-throw and 3-point shooting was the cause for losing game six, it was the knucklehead play of guys like JaVale McGee, Wilson Chandler, and Anthony Randolph that lost them game four. That’s not just the perils of youth. Every team is young. The problem is most serious teams don’t do stupid. The San Antonio Spurs don’t hoard dumb players like they’re going out-of-style. The Memphis Grizzlies don’t harbor a single player lacking in basketball I.Q. The same can be said of the Oklahoma City Thunder, Miami HEAT, Boston Celtics, Golden State Warriors, Houston Rockets and every other team (outside of the New York Knicks) that saw their season extended last week. Blame George Karl all you want, but, those players certainly wouldn’t work for other coaches because they wouldn’t have them. Third, if Denver’s front office thinks they can get away next season without Andre Iguodala’s perimeter defense, then, they have another thing coming. With Iguodala on the floor during the 2012-13 regular season, the Nuggets allowed 100.5 points per 100 possessions — a mark good enough for seventh-overall in team defense. With Iguodala off the floor, that number jumped to 105.3 points per 100 possessions — good enough for 22nd-overall in team defense and not far from their 19th-overall (103.4 DRTG) finish the year before his arrival. Denver was the worst team at defending the 3-ball in playoff history. One less Andre Iguodala means pain. Lots and lots and lots of pain. Fourth, the Nuggets absolutely have to address their gaping hole in the middle. JaVale McGee isn’t the answer. He never was the answer. He should be wearing another uniform by November.

What’s good is a lot of Denver’s players are quite movable. What’s bad is they aren’t movable for much. First, I would recommend trading all of the knuckleheads for draft picks — because you aren’t going to get much of value in return for players who can’t play fundamentally sound basketball when it matters most. Second, I would do everything in my power to ensure Andre Iguodala returns for the 2013-2014 season. If it takes guaranteeing him roster changes and that he be consulted prior to said changes, then I would make such concessions. It is beyond imperative that he return — beyond imperative.

Looking at Denver’s payroll moving forward, JaVale McGee, Wilson Chandler, Andre Miller, Anthony Randolph, and Jordan Hamilton appear to be the most difficult players to move (considering their contracts and relative abilities — or lack thereof). Those five players eat up $25.013 million of Denver’s payroll next season. That’s a ridiculous amount, considering the salary cap is estimated to be just over $58 million. Around 43% of their payroll is guaranteed to players who have no business on a contending team. Andre Miller, for all his faults, can still be moved for something of value. The other four? Not so much. Kosta Koufos, Evan Fournier (his playoff performance notwithstanding), and Kenneth Faried appear to be the most valuable trade chips they have on the table, as Lawson and Gallinari are untouchable. Dangle Koufos, Faried, and Fournier just to see if there are any takers (there probably won’t be). Then go from there.

The playoffs are won with matchups. And until the Nuggets organization figures that out, they will continue to suffer the consequences. The reason Denver advanced to the Western Conference Finals during the 2009 season was because they had advantages at point guard (Chauncey Billups), small forward (Carmelo Anthony), and center (Nene) that were very hard for opposing teams to counter over a seven-game playoff series. They haven’t had the same advantages since. That’s one reason why George Karl’s Nuggets have advanced past the first round only once in his nine years on the job. He just hasn’t had good enough players.

For insight into players Denver should target in the June Draft and during the summer free agency period, check back here every week, as scouting reports and detailed player evaluations are added. As always, thanks for reading.

*Stats for this piece were used courtesy of NBA.com/Stats and Basketball-Reference.com

During the NBA’s draft on June 28, Denver took swing-man Evan Fournier out of France with the 22nd overall pick. I guess Wilson Chandler, Danilo Gallinari, Arron Afflalo, Jordan Hamilton, and Corey Brewer weren’t quite enough to satiate their appetite for wing players. With only Kenneth Faried and Al Harrington on the roster at power forward, common sense would dictate Nuggets brass look for a backup power forward. Jared Sullinger, whom I advocated they take with their first overall pick (if they weren’t going to trade up for Iowa State’s Royce White — who I had no idea would refuse traveling with his team after signing an NBA contract), went to the Celtics immediately after Denver took Fournier.

During the NBA’s draft on June 28, Denver took swing-man Evan Fournier out of France with the 22nd overall pick. I guess Wilson Chandler, Danilo Gallinari, Arron Afflalo, Jordan Hamilton, and Corey Brewer weren’t quite enough to satiate their appetite for wing players. With only Kenneth Faried and Al Harrington on the roster at power forward, common sense would dictate Nuggets brass look for a backup power forward. Jared Sullinger, whom I advocated they take with their first overall pick (if they weren’t going to trade up for Iowa State’s Royce White — who I had no idea would refuse traveling with his team after signing an NBA contract), went to the Celtics immediately after Denver took Fournier.

On this Thanksgiving of 2012, I am thankful for quite a bit …

November 22, 2012 2 Comments

Seeing as how I’m always one to constantly complain about the malaise of my sports teams, I wanted to change things up this Thanksgiving. It’s time to give thanks, be merry, and spread holiday cheer!

I’m thankful for a lot of things this year. I’m thankful to have the peace-of-mind and clarity of thought to even write about basketball right now – if even for free. I’m thankful for the Denver Nuggets. I’m thankful for an NBA franchise to call my own. I’m thankful to have this forum on which to spout my beliefs as if it’s gospel (it isn’t). I’m thankful for every single person who has read something I’ve written and maybe come to a new understanding of the ways in which the world turns (not always correct, but new).

I’m thankful for Ty Lawson’s blinding speed. I’m thankful for 36 year-old Andre Miller and his (hopefully movable) 3-year, $14.65 million dollar contract. I’m thankful for 6-6. I’m thankful for Andre Iguodala’s steady resolve. I’m thankful for “The Manimal”, Kenneth Bernard Faried Lewis. I’m thankful to be able to see Faried every single night he suits up to play for my favorite team. I’m thankful to see him not shrink from the competition of playing the Timberwolves’, Kevin Love.

I’m thankful that a lot of the things I say aren’t taken seriously.

I am thankful for Danilo Gallinari’s monumentally momentous braggadocios swag. I’m thankful for Ohio State grad, Kosta Koufos. I’m thankful for Kosta Koufos? I’m thankful for Kosta freaking Koufos! I’m thankful for Corey Brewer’s locomotive. I’m thankful for Jordan Hamilton’s 44% 3-point shooting through seven games played. I’m thankful for Gallinari and Iguodala’s identical Player Efficiency Ranking (PER). I’m thankful for Timofey Mozgov’s unused brilliance off the bench. I’m thankful for over 7-years of George Karl’s patronage, coaching, ego, and consecutive playoff appearances – and what will hopefully be a continued cancer-free bill of health.

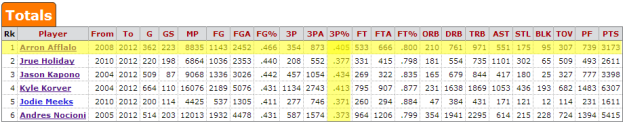

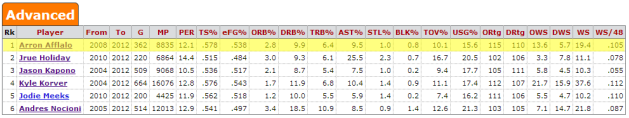

I’m thankful for the services of every Denver Nuggets player past and present – even those who may not have received the kindest of exits. I’m thankful for Carmelo Anthony’s heart-stopping buzzer-beaters. I’m thankful for 33-points in one quarter. I’m thankful for Nene Hilario’s near-decade of service to the city, the franchise, and the community at-large. I’m thankful for Chauncey Billups’ brief return home and the Western Conference Finals that materialized because of his presence. I’m thankful for the brief time Arron Afflalo spent in Denver as a result of Chauncey’s recruitment. I’m thankful for Chris “Birdman” Andersen’s colorful energy, Al Harrington’s inefficiency and locker room chill, Renaldo Balkman’s weed habit, Anthony Carter’s clutch passing, Melvin Ely’s cardboard cutout of Melvin Ely, Shelden Williams’s immense forehead, Kenyon Martin’s amazing tattoo, J.R. Smith’s amazing tattoos, and Malik Allen’s cardboard cutout of Malik Allen. I’m thankful for Joey Graham. Wait, who?

And I will forever be thankful for Mr. Frenchie, Johan Petro.

I’m thankful for 4-points, 14-rebounds, 4 turnovers, and six personal fouls in 35-minutes and 26-seconds. I’m thankful for sobriety.

I’m thankful for people even humoring me into listening to what I have to say.

I’m thankful for Tad Boyle. Praise be to Jesus, I’m thankful for Tad Boyle. I’m thankful for Josh Scott’s post presence and free-throw shooting. I’m thankful for Askia Booker’s confidence and leadership. I’m thankful for the rebounding tenacity of Andre Roberson and the bright future of Xavier Johnson and Spencer Dinwiddie. I’m thankful for the #23 ranking in the latest Associated Press poll – 15 years in the making. Look ma, it’s the real deal!

I’m thankful for Jon Embree and any man willing to take on the responsibility of rebuilding a once-proud college football powerhouse from the depths of despair.

I’m thankful for Peyton Manning. I’m thankful for Von Miller and Elvis Dumervil. I’m thankful for Willis effing McGahee. I’m thankful for Brandon Stokley, Demariyus Thomas, and Ronnie Hillman. I’m thankful for Von Miller and Elvis Dumervil again. I’m thankful for John Elway and Pat Bowlen and John Fox and Jack Del Rio. I’m thankful for Peyton fucking Manning.

I’m thankful for the end of Tebow-mania.

I’m thankful for the pick-and-roll. I’m thankful for the Triangle, the Princeton, and the Motion offense. I’m thankful for Steve Nash skip-passes. I’m thankful for Rasheed Wallace blind-passes out of the post. I’m thankful for J.R. Smith pull-up jumpers in transition. I’m thankful for Dirk Nowitzki operating out of the high-post. I’m thankful for Carmelo Anthony – starting power forward. I’m even more thankful for everything he does on a nightly basis despite never getting enough respect from NBA officials. I’m thankful for Paul Pierce’s mid-range game. I’m thankful for Rajon Rondo’s developing jumper. I’m thankful for Jason Terry’s airplane spin and Ray Allen’s buzzer-beating 3-pointers on the wing. I’m thankful for Chris Paul-to-Blake Griffin alley-oops. I’m thankful for Jamal Crawford. I’m thankful for Portland Trail Blazers fans. I’m thankful for Damian Lillard. I’m thankful for Andre Miller’s lob passes and post-game and “savvy veteran leadership”.

I’m thankful for the coaching mastery of Doug Collins, the smooth shooting of Kevin Martin, and the end of Linsanity.

I’m thankful for Klay Thompson.

I’m thankful for the genius of the San Antonio Spurs. I’m thankful for Tim Duncan’s Hall-of-Fame career, Manu Ginobili’s Euro-step, the fancy footwork of Frenchman, Tony Parker, and the immutable Gregg Popovich’s class, crass, and sass.

I’m thankful for Mike Dunlap and the emerging brilliance of Kemba Walker. I’m thankful for Zach Randolph and the likely Jared Sullinger comparisons I make in the future. I’m even thankful for Gerald Wallace and Brook Lopez, interestingly enough.

I’m thankful for Kobe Bryant’s renaissance.

I’m thankful for the unmatched and untouched and unmitigated dominance of one LeBron Raymone James.

I’m thankful for the Wages of Wins stat geeks. I’m thankful for Matt Moore and the rest of the unrelenting taunting, trolling ignoramuses on Twitter.

And I’m thankful for you.

Thank you for reading. Thank you for arguing. Thank you for being there. Thank you for everything.

Happy Holidays. Go Nuggets!

I will always be thankful for this:

Share this:

Filed under Commentary Tagged with Al Harrington, Andre Iguodala, Andre Miller, Andre Roberson, Anthony Carter, Arron Afflalo, Askia Booker, Blake Griffin, Brandon Stokley, Brook Lopez, Carmelo Anthony, Chauncey Billups, Chris "Birdman" Andersen, Chris Paul, Corey Brewer, Damian Lillard, Danilo Gallinari, Demariyus Thomas, Denver Nuggets, Dirk Nowitzki, Doug Collins, Elvis Dumervil, George Karl, Gerald Wallace, Gregg Popovich, J.R. Smith, Jack Del Rio, Jamal Crawford, Jared Sullinger, Jason Terry, Joey Graham, Johan Petro, John Elway, John Fox, Jon Embree, Jordan Hamilton, Josh Scott, Kemba Walker, Kenneth Faried, Kenyon Martin, Kevin Love, Kevin Martin, Klay Thompson, Kobe Bryant, Kosta Koufos, LeBron James, Linsanity, Malik Allen, Manu Ginobili, Melvin Ely, Mike Dunlap, NBA, Nene Hilario, Pat Bowlen, Paul Pierce, Peyton Manning, Portland Trailblazers, Rajon Rondo, Rasheed Wallace, Ray Allen, Renaldo Balkman, Ronnie Hillman, San Antonio Spurs, Shelden Williams, Spencer Dinwiddie, Steve Nash, Tad Boyle, Thanksgiving, The Manimal, The Princeton Offense, The Triangle, Tim Duncan, Timofey Mozgov, Tony Parker, Ty Lawson, Von Miller, Wages of Wins Network, Western Conference Finals, Willis McGahee, Xavier Johnson, Zach Randolph